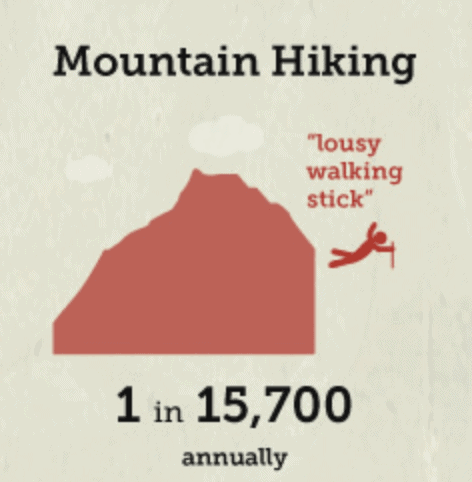

As my big backpacking trip was less than three weeks away, I decided to start thinking seriously about trail safety and how to stay alive. Shortly into my research I realized, hiking might be a little more dangerous than most people expect.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, your chance of dying while mountain hiking is 1 in 15,700 annually, or a .0064% chance… this doesn’t seem to too bad until you compare it to, say… skydiving, where your chance of dying is 1 in 101,083, or .00099%. That’s right, you’re 6.4x more likely to die while hiking than you are while skydiving.

What’s making hiking so much more dangerous than skydiving? Of course, the obvious answer is bears. You seldom, if ever, encounter a bear while plummeting towards the ground at 120 MPH, whereas bears are constantly eating hikers on trails as if they are at a sushi bar, pulling treats onto their plate as they drift by on small boats. As I went to confirm my hypothesis, I realized that bears are pretty much the only thing that isn’t going to kill you while backpacking. So, statistically speaking, what was the most likely thing to prematurely re-route my backpacking trip to the hereafter?

I was unable to locate a definitive source of hiking or backpacking deaths only. The American Alpine Club publishes and annual Accidents in North American Mountaineering report, but that doesn’t address hiking specifically. I found a promising article, What’s Killing America’s Hikers? but the statistics were around search and rescue reports and summarized the primary causes as lack of knowledge, lack of experience, and poor judgment, whereas I was really hoping for categories like “eaten by a bear”. A final source of inspiration for fear was 17 Things Scarier Than Bears On The Pacific Crest Trail, which didn’t provide statistics but did help expand the breadth of options for concern.

I pieced together what seem to be the specific categories of risks that actually sound frightening (really, you’re never going to see a movie, Friday the 13th: Lacking Knowledge, or Scream: Poor Judgment). Here’s my assessment, in countdown order:

7. Animals

I’m counting down from least risky to most, so as much as I want to blame bears, they are pretty much bottom of the deadly risk list and only made the list because they are grouped with all of the other animals that can kill you, including (but not limited to) mountain lions, snakes, mosquitos, spiders, and bees. Each animal requires a different risk mitigation strategy, and sometimes requires that you quickly classify the variety of the species about to attack you, since the same strategy applied to the wrong species can lead to provocation rather than being a deterrent. As you’re being mauled, be sure to check if it is a grizzly bear or a black bear before taking any action.

6. Temperature (too much, too little)

If you get too hot, your brain starts cooking. The good news is you probably won’t notice, because you’ll be more interested in your convulsions, except you might not notice the convulsions because you’ll be delirious.

On the other hand, cold can happen very quickly as sudden changes in weather can result in severe temperature drops in a matter of minutes. You also experience a state of delirium, making very poor decisions and often coming to the conclusion that you are too hot – many freezing victims are found outside of their shelter and in a state of disrobe, potentially giving new meaning to the phrase, “frozen stiff”.

5. Lightning

Lightning has the advantage of range when it comes to contributing to an untimely death, making you generally unsafe within 6 miles but strikes have been recorded at distances of 10 miles. In the US, lightning kills about 50 people each year, about 11 of those are in Colorado. There are numerous tips to reduce your chances of being struck by lightning, but if you’re not minutes away from being inside a properly-grounded building or vehicle, most of the tips just lead to variations of an, “oh shit” scenario. And you might not even go out with a glorious bolt of lighting reaching from the sky to your body… 50% of lightning induced injuries and death come from ground current and an additional 30% from side splash, where lightning jumps from person (or object) to person, so death can happen as far as 60 feet from where lightning strikes the ground.

4. Health Issues

While hypothermia, heat stroke and bleeding from the neck while a mountain lion eats you are arguably health issues, I’m placing things like heart attacks, ruptured appendix, and spreading infections in this category. All of the health issues that have a high recovery rate if you can seek prompt medical attention can become life or death issues when isolated in the woods. As a solo hiker you’re screwed, with a companion you also probably screwed. Since dysentery is both a health issue and can be the result of drinking untreated water, I will blend this with the next highest risk…

3. Water (not enough)

Not enough drinkable water can kill you in a few ways. Continuing on with the general “health issue”, water than has not been properly treated or filtered can give you a variety of health problems, a common one being the Giardia parasite . Of course there’s the more obvious problems caused by lack of drinkable water, dehydration and the follow-up problems leading to death, heat stroke and hypothermia. If you’re thinking that hiking in cold weather reduces this risk, not so much… cold, dry weather can use more water than warmer, more humid air and you may require even more water.

2. Water (too much)

If not having enough water was going to kill you, having too much water, especially when it is surrounding your body, is even more likely to kill you. Evidently a surprising number of hiking deaths result from bodies of water making it difficult for gill-less hikers to breathe, smashing hikers into other objects, or causing hikers to free-fall off waterfalls. Most of this time the body of water presents itself in an obvious fashion and bad choices lead to death, but occasionally flash floods can make death more or a surprise.

1. The Ground (falling into it)

A few years ago I hiked Half Dome in Yosemite. The park averages 12-15 deaths each year, although the Mist Trail takes a lot of the credit, especially as tired hikers return from Half Dome and glide off slippery rocks. As I was ascending the cables, I couldn’t help but think that a slip and fall would be several thousand feet before I landed quite abruptly in the Yosemite Valley, but would be preceeded by most of the flesh being scraped off my body as I slid across about 250 feet of steep granite… too slick to get traction, just abrasive enough to take skin samples on my journey, possibly making meeting the valley floor a welcome relief. It made me hold the cables that much tighter.

If anybody has reliable data sources they can cite, or if you just happen to be super knowledgable about hiking death statistics and suggest a re-ordering, please leave a reply!

Update: I found Forget bears: Here’s what really kills people at national parks, which has some statistics for national parks, not hiking in general, and seems largely consistent with my assessment, adjusting for activities engaged in by most visitors to national parks.