I’ve generally found that every time I have dealt with stock options I’ve learned something new, and usually in somewhat painful ways. It’s one of the few areas where I actually hope I’ll someday understand every aspect and stop learning, but changes to how options are handled and complicated (and changing) tax laws promise to make stock options a topic that will never be mastered.

In my most recent experiences, I learned a few things that I don’t seem to be common knowledge, even by many people that have been in the stock option rodeo for a long time.

Companies Can Outlive Their Stock Plans

The stock options granted to employees, directors, advisors, or other parties are done so pursuant to a stock plan that is typically created around the time of incorporation. When one receives an option grant, the grant will reference the stock plan and a copy of the plan should be made available to the recipient of the grant. These stock plans have a lifetime, with 10 years being pretty common, and the ability to exercise options typically expires with the stock plan.

And for what I’m guessing is more than 99% of Silicon Valley companies, the 10 year life of the stock plan is irrelevant because, within 10 years the company most likely fails or has a major restructuring of the cap table (making the options worthless), gets acquired, or goes public (resulting in some conversion or liquidity of the options). In almost every case the stock options either get flushed down the toilet or become liquid within 10 years. But, there is a less common scenario… a company substantially increases in value and remains private and independent, celebrating 10 years and outliving the initial stock plan.

In this situation, most people granted options under the original stock plan need to exercise or forfeit their stock (there is typically a way to handle current employees as a new plan is adopted). And, that’s the big gotcha. When granted stock options, a lot of people will chose to not exercise their options until there is a liquidity event, so they don’t risk any up-front expense and only purchase when they can immediately sell the stock for the gains (this strategy eliminates up-front risk, trading for a less favorable tax liability later, assuming the company doesn’t fail).

So let’s put some numbers behind this… Ned joins the advisory board of a startup company during the seed round and gets 100,000 options valued at $0.01 (one cent) each, so Ned can purchase these 100,000 shares for a total of $1,000, but doesn’t do so at the time of the grant. Against all odds, the startup does well, survives 10 years without a liquidity event and the shares are now worth $1.25 each – 125x return! Ned gets a call and is told that the stock plan is about to expire and he must exercise his options or lose the grant. The good news is, $1000 to get $125,000 in stock is a pretty good deal. However, that purchase is going to be a taxable short-term gain of $124,000 (10% – 39.6%, depending on Ned’s total taxable income, so up to $49,104 to be paid in taxes). But, the company is still private so there is not necessarily a market where Ned can get liquidity, so in rough numbers Ned just spent $50,000 in cash to buy $125,000 in stock that can’t be sold – that doesn’t sound all that bad, but there are a lot of factors that prevent it from being an easy decision. Another big rub for many is, instead of the company getting the money from the stock purchase, it goes to the government.

While there are plenty of stock option scenarios that present a similar dilemma, the stock plan end-of-life scenario is unique in the lack of flexibility – even if the company and grant holder want to find a solution, there isn’t a clean way to update paperwork or give extensions for exercising at the end of the stock plan’s life.

There is a very easy way to avoid this early on… if Ned exercised when he received the grant, he would have paid $1,000, the fair market value for the stock, with no tax consequence, and 10 years later he would already own that stock, now worth $125,000 (but still not liquid).

My best advice (worth everything you just paid for it, so consult a lawyer or tax expert before following it) is to exercise as early as possible, especially in a startup where the stock barely has value. Your time is the most valuable thing you have, so if you’re willing to bet on the startup by investing your time, you should be willing to bet some cash, too.

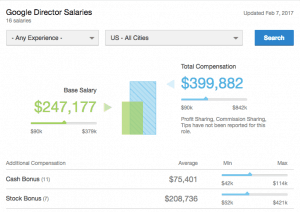

Most Job Seekers Don’t do the Math

At this point in my life I’ve overseen more than a thousand job offers, and one aspect that surprises me is how frequently prospective employees don’t ask for the information necessary to understand the value of the stock options offered as part of their compensation package (sometimes as a very material component of that package). I’ve had conversations where job seekers told me another company offered them twice as many options as I was offering (seeking more from my offer), but they didn’t know the total options in either company or recent valuations, so they didn’t understand the percentage of ownership (if you’re offered 1 share of Berkshire Hathaway or 1000 shares of Apple, you’ll make $117,000 more taking the Berkshire Hathaway). Seeing so many people not doing this math has lead me to joke that my next company will start with one trillion shares of stock so that I can offer more stock than every other company.

Employees not understanding this component of their compensation creates an interesting challenge for an employer… I believe companies should help employees understand the value of stock options and the various nuances of how options work. However, I also believe that it wastes a limited resource to provide stock options when an employee doesn’t value them. I like everybody to have a stake in the outcome of the company, but options should be weighted so they are the most valuable to the recipient, and other forms of compensation should be used when options are not valued.

Employees not understanding this component of their compensation creates an interesting challenge for an employer… I believe companies should help employees understand the value of stock options and the various nuances of how options work. However, I also believe that it wastes a limited resource to provide stock options when an employee doesn’t value them. I like everybody to have a stake in the outcome of the company, but options should be weighted so they are the most valuable to the recipient, and other forms of compensation should be used when options are not valued.

If you’re interested in the details about understanding stock option compensation and what questions to ask when comparing offers, there are some detailed guides I reference below.

Small Business Stock Capital Gains Exclusion

Another (very pleasant) surprise I learned about was Section 1202, which excludes from gross income at least 50% of the gain recognized on the sale or exchange of qualified small business stock (QSBS) that is held more than five years. The latest amendment to Section 1202 provides for 100% of any capital gain (up to $10 million) to be excluded if the small business stock was acquired after September 27, 2010.

Section 1202 is surprisingly not well known – four Bay Area tax advisors I contacted were unaware of it when I referenced it. Fortunately it was mentioned in Piaw Na’s book, An Engineer’s Guide to Silicon Valley Startups, where the talented and helpful Chad Austin discovered it and shared the knowledge.

Section 1202 is surprisingly not well known – four Bay Area tax advisors I contacted were unaware of it when I referenced it. Fortunately it was mentioned in Piaw Na’s book, An Engineer’s Guide to Silicon Valley Startups, where the talented and helpful Chad Austin discovered it and shared the knowledge.

I won’t go into details, but if you sell startup stock that you held for 5 years, this can be a material tax savings for you. This is yet another reason to exercise early, since you need to hold the stock, not the options.

Great Resources for Learning About Stock Options

If you’re looking for a comprehensive overview of stock options – I suggest the very excellent Introduction to Stock & Options by David Weekly, or the also very excellent The Open Guide to Equity Compensation by Joshua Levy and Joe Wallin.

Did I get it wrong? Is there another stock option gotcha that I missed? Please leave a comment!