If you’ve ever wanted to see a figurine of yourself but you have no artistic talent, AI image generation can make that dream come true, and you can try it for free. I jump right into the “how to” and add my boring commentary to the end of this post, so you can skip it.

I’m using DALL-E for my image generation which requires a paid subscription, but you can get free access to it through Microsoft Bing Image Creator (requires a free Microsoft account). Once you have signed in, look for the text input field next to the two buttons “Create” and “Surprise Me”. The text field is where you describe what image you want AI to generate, then you click “Create” and a few seconds (or minutes) later, up to four images will be displayed. This process is called “prompting”, which is a common way to guide AI to generate the desired output. But getting AI to do exactly what you want is a little like herding drunk cats, so crafting the prompt can take some effort and some understanding of how things work under the hood. We’ll skip that for now and just start making fun things…

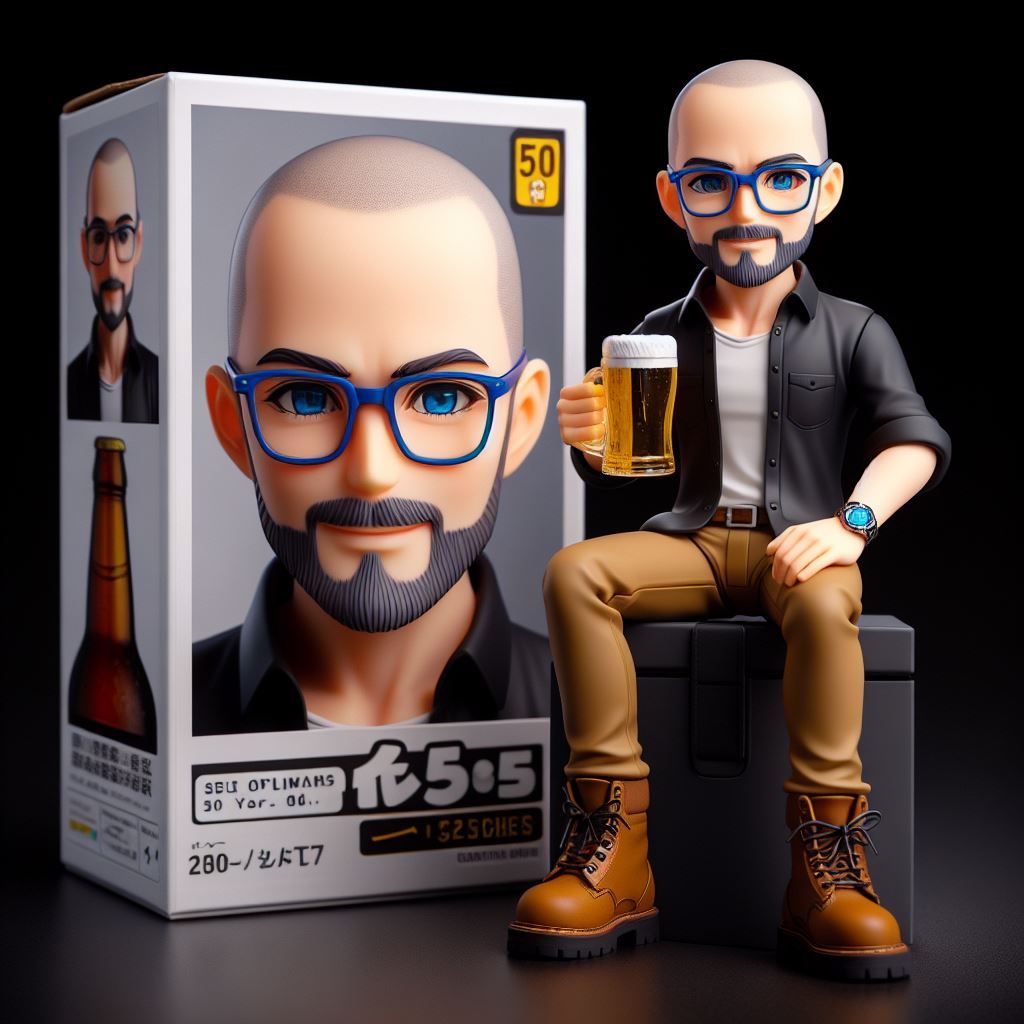

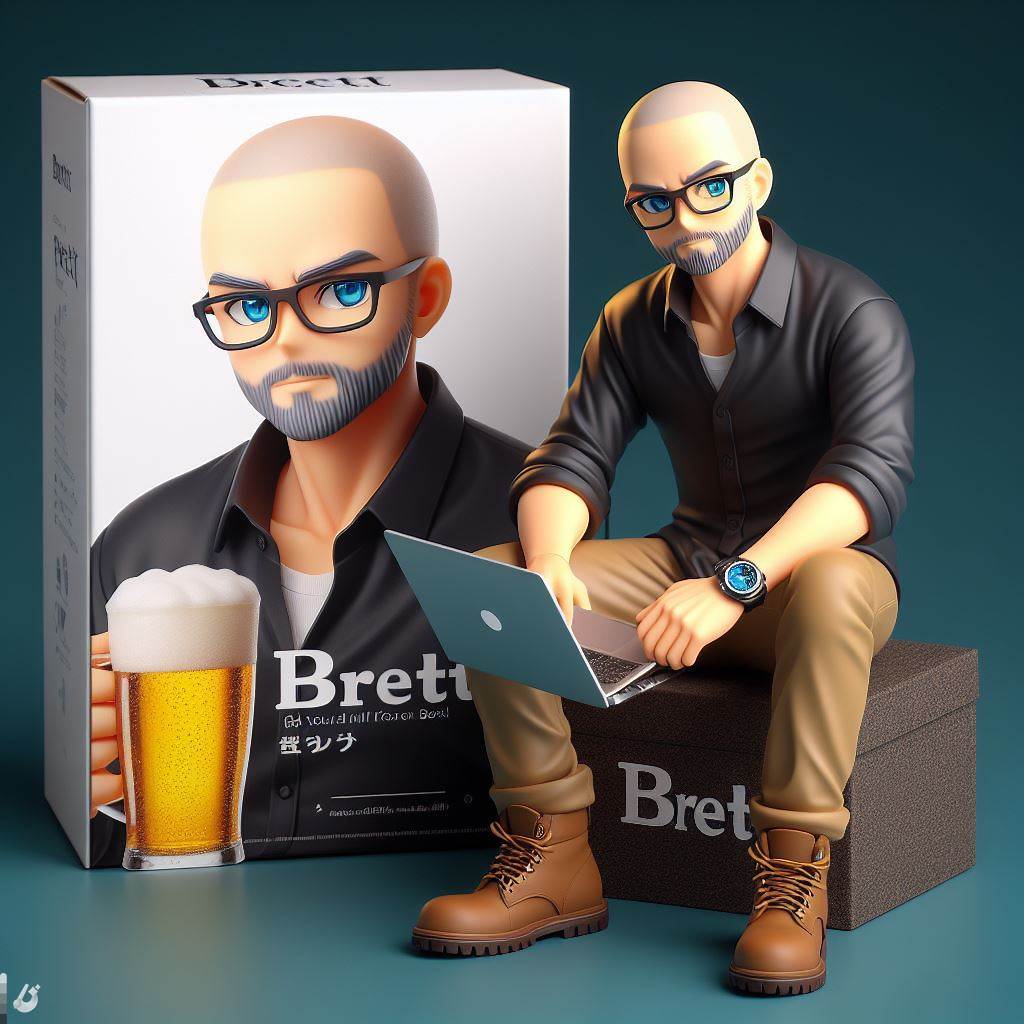

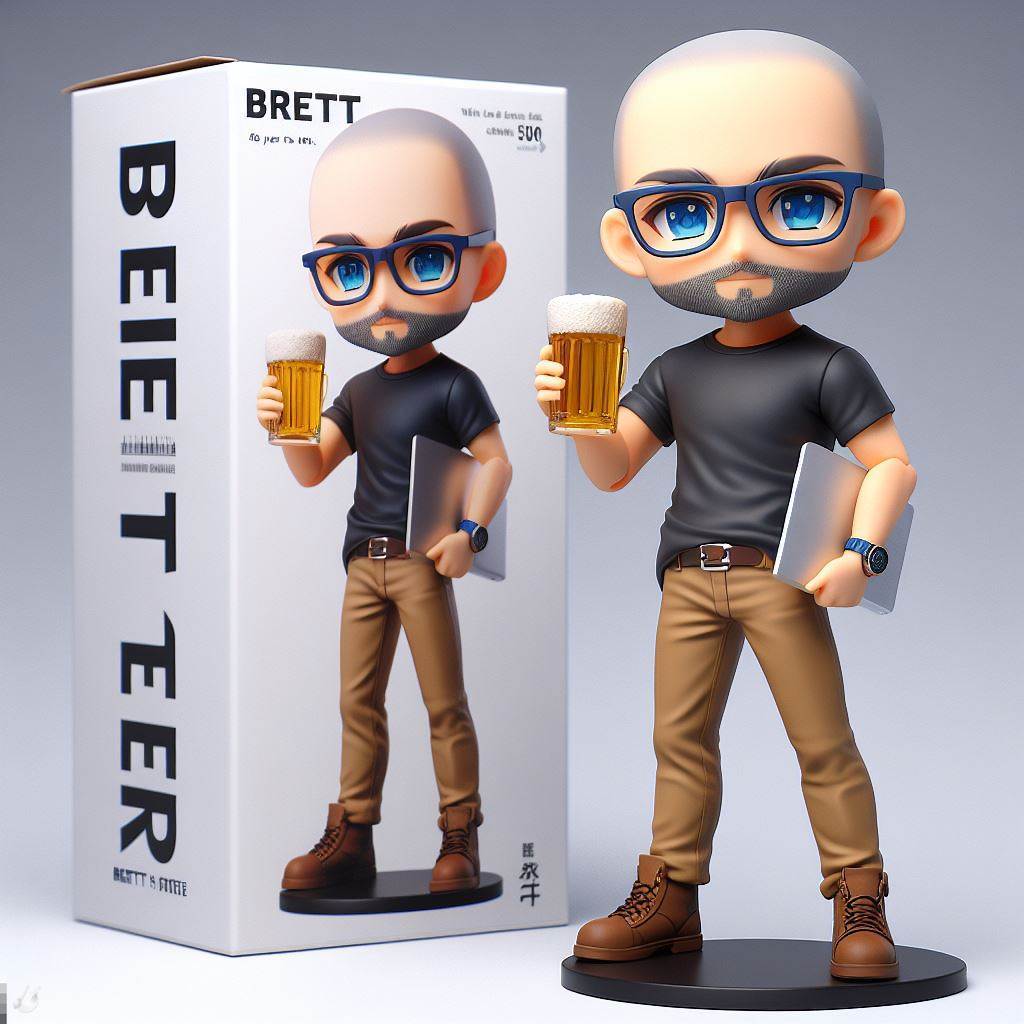

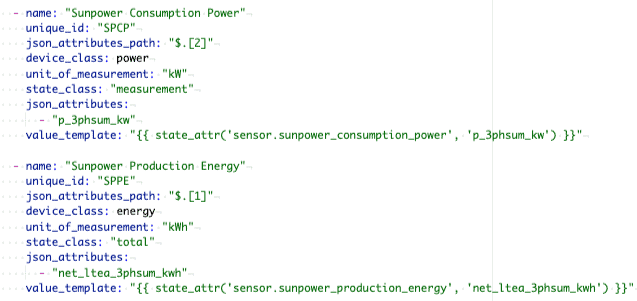

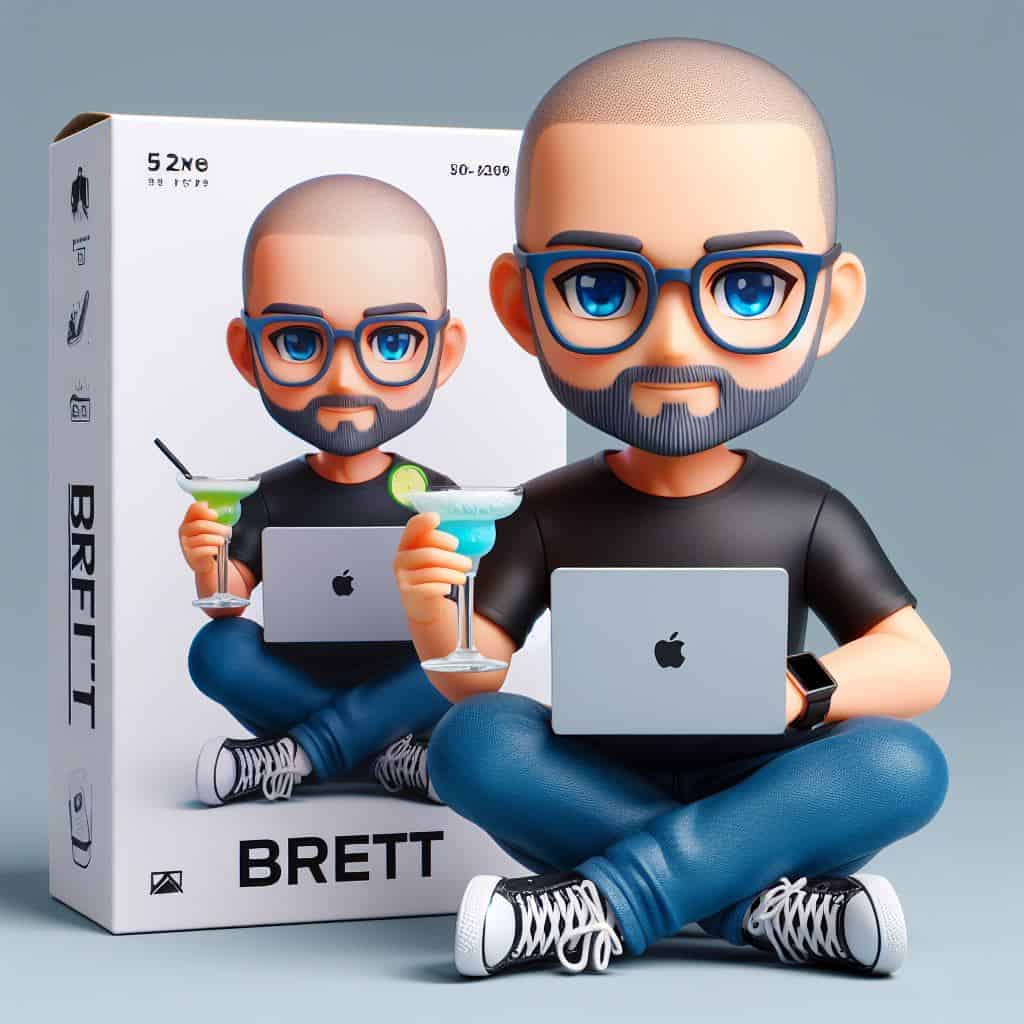

The structure for the prompt is “Anime figurine of <my description, skin tone, eye color, hairstyle, outfit>. The figurine is displayed inside a box with <text on box> and logo for the box, allowing visibility of the figure, typography, 3D render”. To make something that looks sort of like me, I used “Anime figurine of a shaved head, bald on top, nerd, white skin tone, dark gray hair, blue eye color, brown short beard, brown eyebrows, black shirt, jeans, Converse high tops, wearing blue rimmed glasses, wearing a watch, holding a laptop and a margarita. The figurine is displayed inside a box with Brett and logo for the box, allowing visibility of the figure, typography, 3D render“

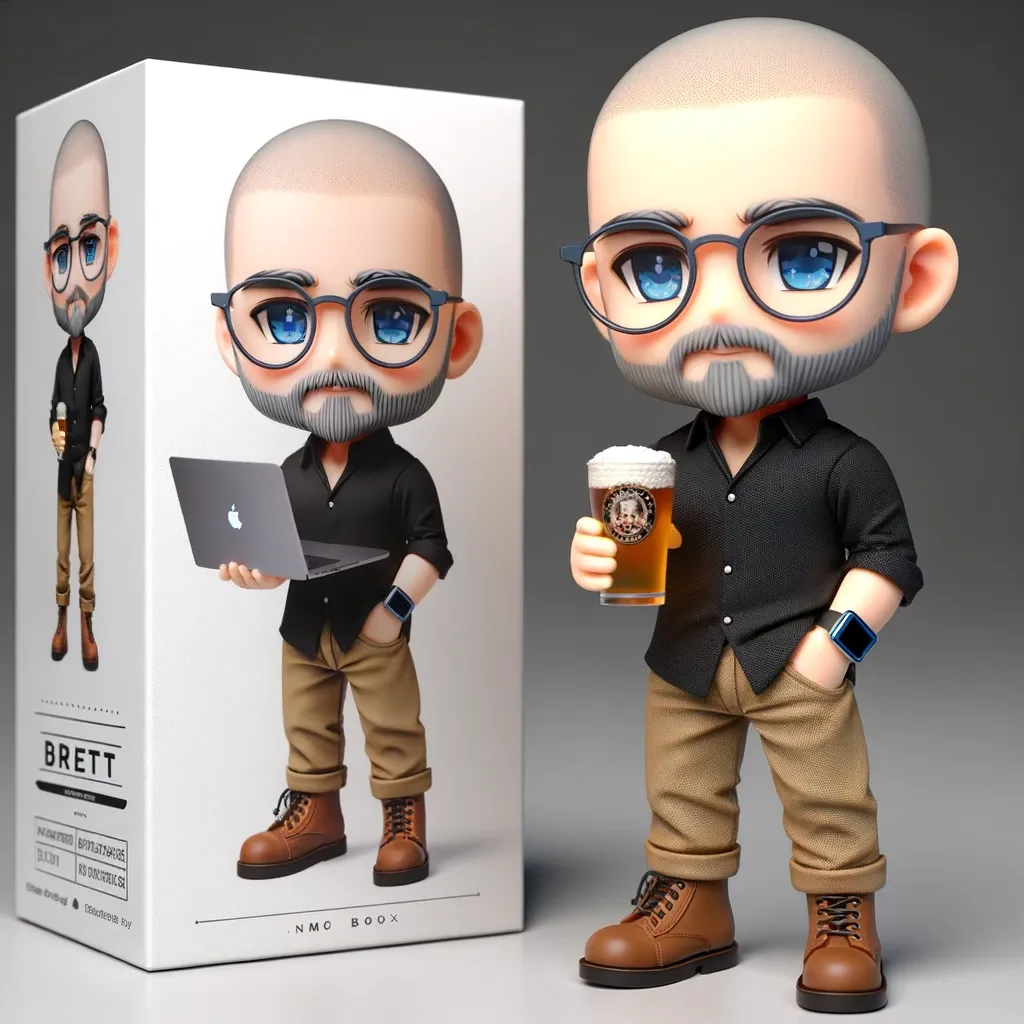

Once you’ve tried this for yourself, you probably noticed a few things… Most obviously, somehow the AI didn’t do what you thought you told it. For example, while I prompted “bald on top“, one of my images clearly had hair, which might be the AI getting confused with the conflicting “dark gray hair” in the prompt. I have found replicating hairstyles, even bald hair styles (if… that’s a hair style?), can be challenging. I’ve yet to be able to get any consistency with hair only on the sides and back of the head. The other thing you will probably notice is the wild things that can show up in the image, especially when it comes to text generation, where AI tends to get… creative. Some of the words you use in your prompt may show up in the image, and misspelling is not uncommon.

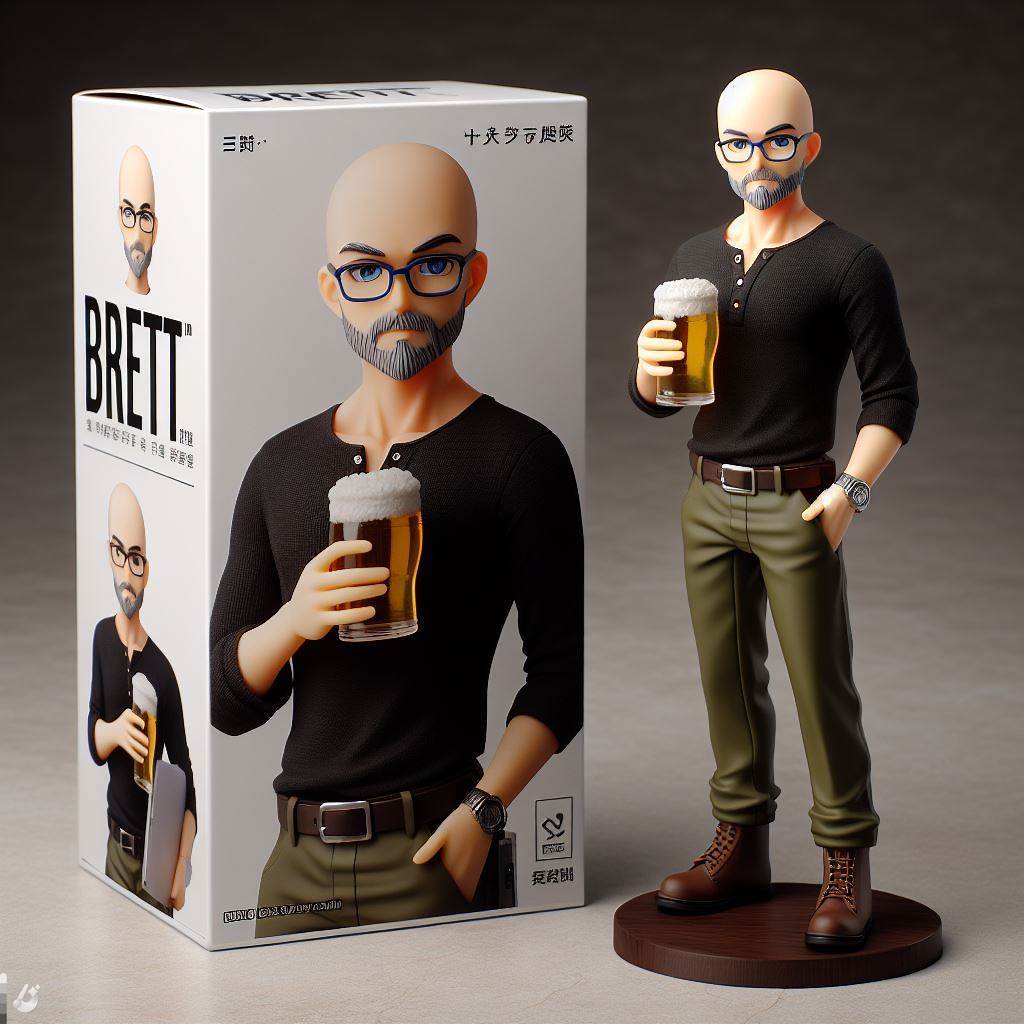

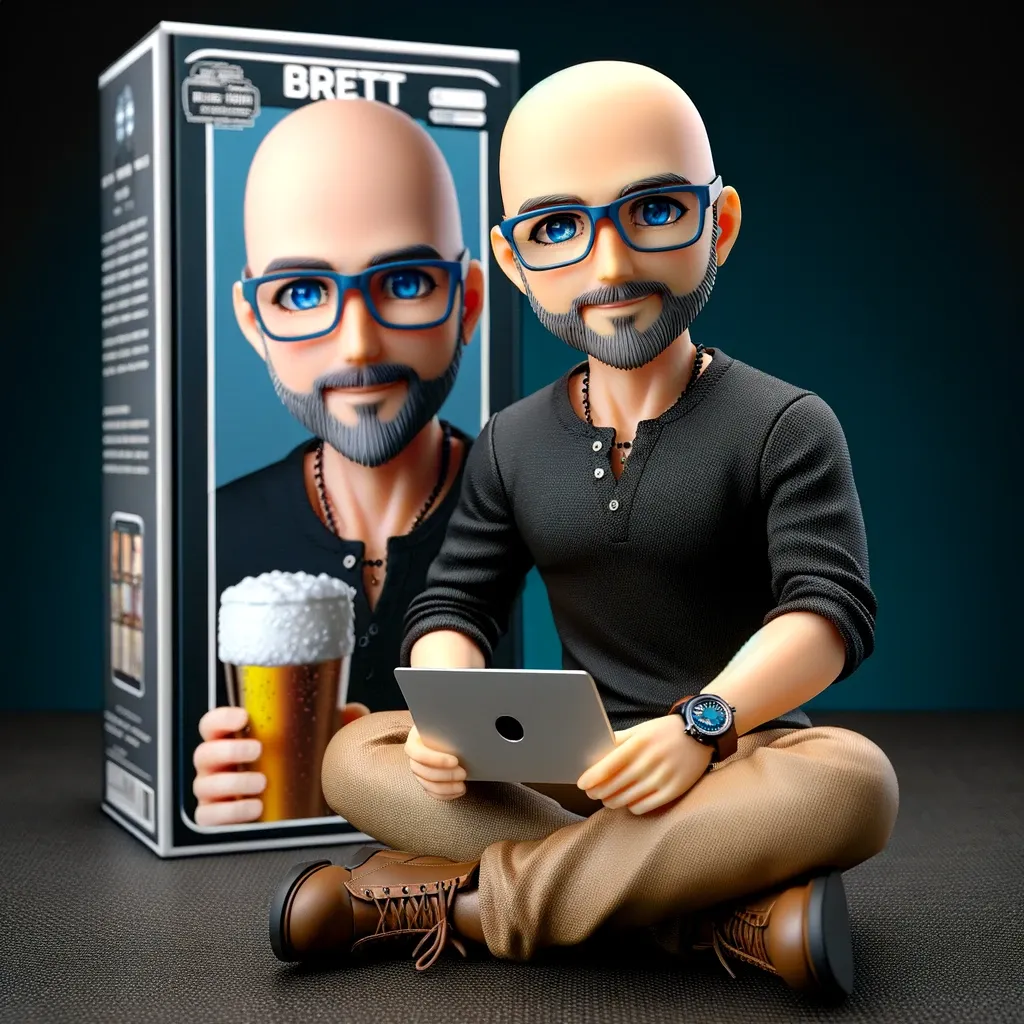

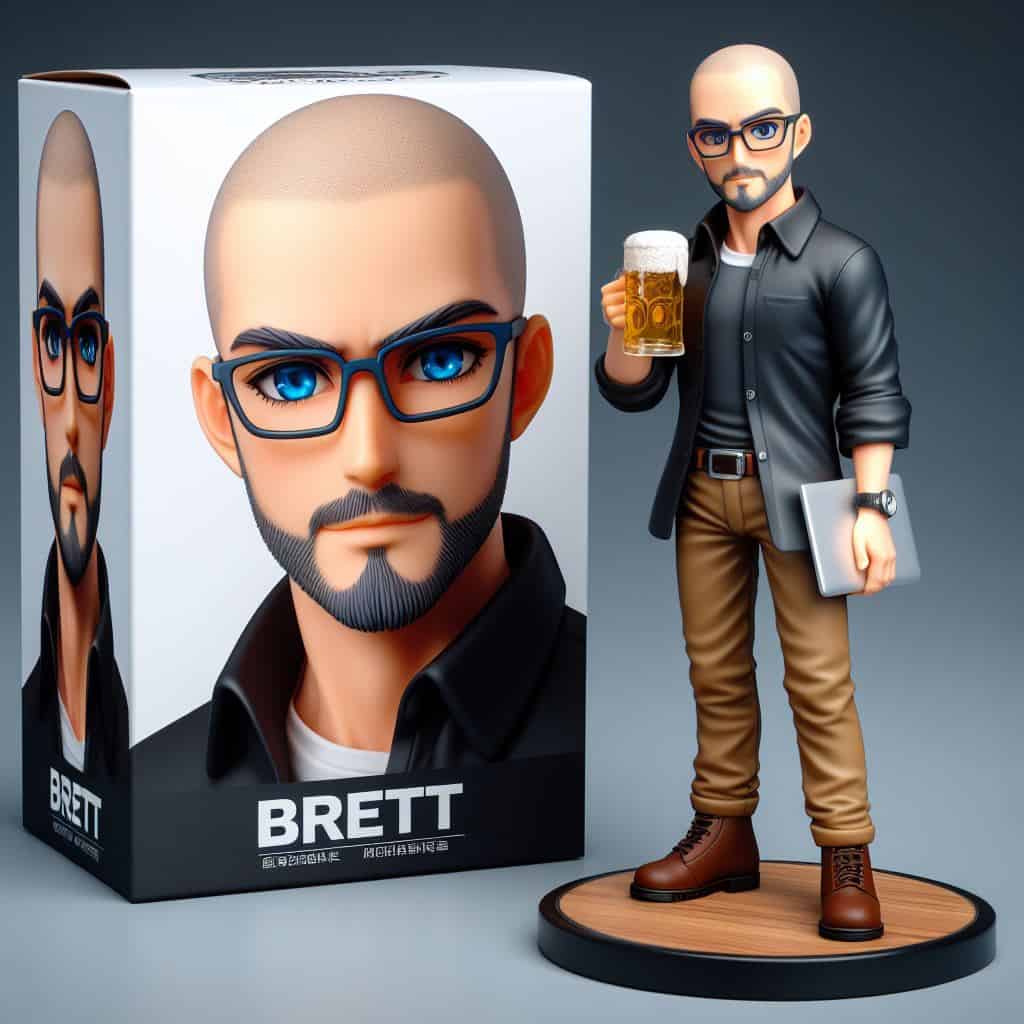

There is considerable variation in the images, some looking more like the giant-headed Funko Pop figurines, and others having pretty realistic proportions. Prompting for another common outfit I wear, “Anime figurine of a shaved head, bald on top, nerd, white skin tone, dark gray hair, blue eye color, brown short beard, brown eyebrows, black shirt, tan pants, brown leather boots, wearing blue rimmed glasses, wearing a watch, holding a laptop and a pint of beer. The figurine is displayed inside a box with Brett and logo for the box, allowing visibility of the figure, typography, 3D render” created something a little more proportional.

So play around a little and see what you get… if anime isn’t your thing and you really love the Funko Pop style, try swapping out the prompt, “Funko style figurine of a shaved head, bald on top, nerd, white skin tone, dark gray hair, blue eye color, brown short beard, brown eyebrows, black shirt, jeans, Converse high tops, wearing blue rimmed glasses, wearing a watch, holding a laptop and a margarita. The figurine is displayed inside a box with Brett and logo for the box, allowing visibility of the figure, typography, 3D render“.

This gallery contains more examples:

Boring Commentary

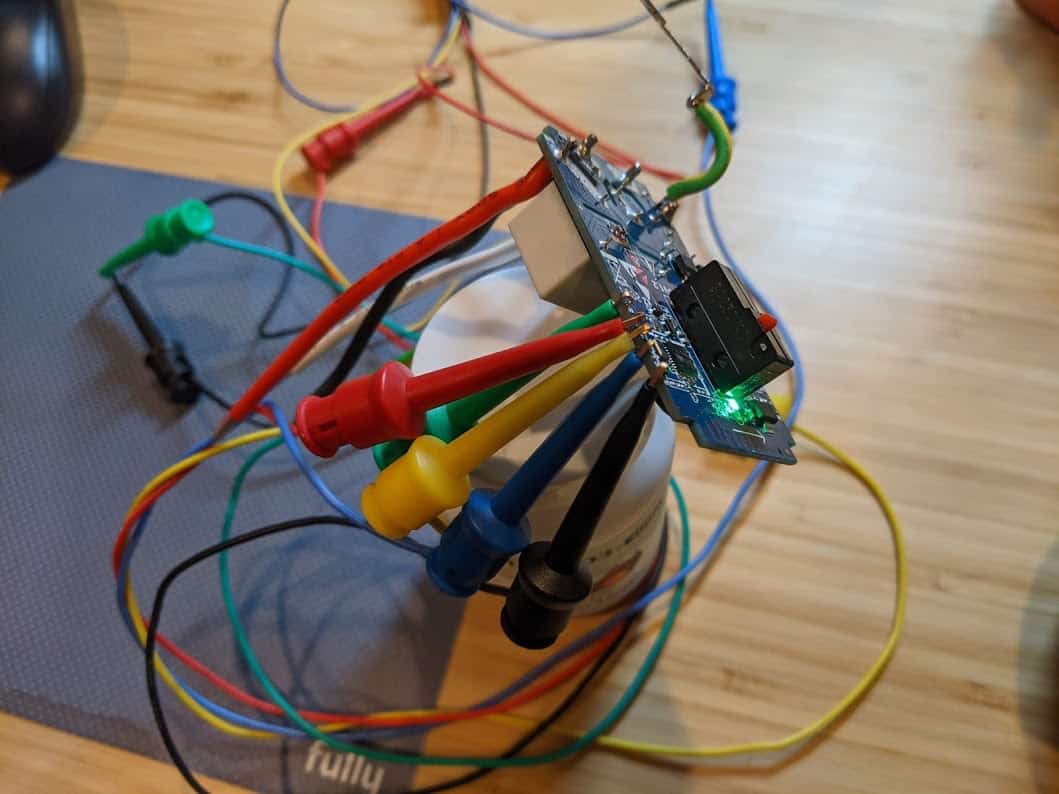

A little over a year ago I wrote Robots Building Robots: AI Image Generation, where I used my laptop for AI image generation, meaning I had to use substantially less powerful AI models than are available in the cloud, where processing power and memory can be massive. The less powerful model was fine for the specific application I had in mind (a cartoon-like sketch of a robot for a sticker), but a few people commented that the quality of the AI images was average, and some were skeptical about AI’s capability.

In that same post, I mentioned Midjourney, which at the time version 4 was just coming out and already looking pretty amazing. In the 14 months since then, the quality and capability has continued to improve at an astonishing pace. For a detailed look at Midjourney specifically, check out this post from Yubin Ma at AiTuts. In less than two years, this model has gone from distorted human faces (some almost unrecognizable) to photo realism.

I have been surprised by both the rate at which the quality and the versatility of AI generated images has increased, with the anime figurines being one of the more recent (and delightful) examples of something AI can create unexpectedly well. I’m limiting this post to still image generation, but the same is happening for music, video, and even writing code (my last three hobby programming projects were largely created by AI). It’s reasonable to assume that AI will make substantial improvements to generating 3D image files, so soon you’ll be able to 3D print your cool little anime figurine.

There are, of course, significant implications of having computers provide a practical alternative to work that used to require humans, and much like the disappearance of travel agents once the Internet democratized access to booking travel, we should expect to see a dramatic reduction in demand for human labor, and this will be disruptive and upsetting… some professions will be nearly eliminated. I don’t want to be dismissive about the human impact of more powerful automation.

At the same time, AI can empower people, and create entirely new opportunities. Large language models (LLM) create the opportunity for customized learning, where eventually individuals all across the planet can have a dialog with an AI teacher, navigating millions of human years of knowledge. More and more, people will not be limited by their resources, they will only be limited by their ideas… The average person will be able to build a website, or a phone app by describing what they want, and someone considering themselves as “not artistic” will be able to create songs, artwork, or even movies that will eventually be box office quality. AI will also likely play a significant role in things like medical advances and energy efficiency, things we generally consider good for humans.

Did you enjoy making yourself into an anime figurine? Did you come up with a prompt that made a super cool image? Did you figure out how to get my male pattern baldness accurate on the figurine? This my hot take on being optimistic about AI is horrible? Leave a comment, below!