Firing people is perhaps the most unpleasant responsibility that comes with being a manager. I’ve read many articles on “the right way” to handle firing, but my experience has taught me every case is different, and even following the best advice can result in a challenging interaction.

I’ve created guidelines for myself that feel fair (this is how I want to be fired), and I accepted that firing is unpleasant for everybody involved, so it’s ultimately about making the best out of a shitty situation.

My guidelines come from the perspective of a culture I want to see in a company, not the legal perspective (which tends to err on the side of corporate protection over recognizing the human components).

Guidelines for a Firing Manager

My guiding principle, be respectful, helping the employee retain their dignity, drives these guidelines:

- Always remember you’re firing a person, not a resource. In almost every case being fired is an emotionally painful situation, and being mindful that you are firing a person, with feelings, fears, and personal responsibilities that will be compromised as a result of job loss. People react unpredictably in emotion-filled situations. As the firing manager it is important to be respectful through the whole process and be balanced in responses to the other person’s (re)actions.

- Don’t get into a detailed discussion. A common pattern is the person being fired will want to get into the details about the decision to fire. The firing discussion should be efficient (there is nuance in balancing not being insensitively fast vs. dragging out the pain). The manager should absolutely provide a high-level explanation, and the next steps (ideally the company has a standard document that explains the issues that will be important to the employee), but the person being fired is very unlikely to actually hear a detailed discussion – they are too emotional to process it. If a person being fired wants to get into details, I suggest scheduling coffee the following week, giving them enough time to figure out what questions are really important and getting past the initial shock so they can be receptive to the answers.

- Never discuss individual details with others. When a person is fired, other employees frequently want to understand more details. It can be tempting to want to bring others into the loop or calm an underlying “am I next?” fear they may have by sharing the details, but it is disrespectful to the person being fired (it’s also probably a liability for the company). Instead, have a culture that is transparent about the process (why and how) people are fired, while never discussing an individual’s specific situation.

Reasons for Firing

The reasons for firing an employee generally fall into three categories: performance, role eliminated, and violating the company relationship. Each impact the person being fired, other employees, and possible outcomes differently.

Performance Problems

When an employee is under-performing it is their manager’s responsibility to make that employee successful and, if that fails, fire the employee. An employee’s performance should be a regular discussion with their manager, and missing expectations should be made explicitly clear, along with clarity around the exact expectations and a plan to improve. If the improvement doesn’t happen, the firing discussion should be more of a final conclusion to the mutual recognition of the problem, with both parties aligned on the shared data. My rule is, “if the employee was surprised they were fired for performance reasons, this is a failure of their manager”.

When an employee is under-performing it is their manager’s responsibility to make that employee successful and, if that fails, fire the employee. An employee’s performance should be a regular discussion with their manager, and missing expectations should be made explicitly clear, along with clarity around the exact expectations and a plan to improve. If the improvement doesn’t happen, the firing discussion should be more of a final conclusion to the mutual recognition of the problem, with both parties aligned on the shared data. My rule is, “if the employee was surprised they were fired for performance reasons, this is a failure of their manager”.

Role Change

The role change scenario is one where the company’s requirements or constraints have changed and an employee is no longer appropriate for the role. I’m including layoffs / downsizing in this category (not being able to pay people is a constraint). A commonality in these firings is it includes qualified, successful employees. This is the one firing scenario where additional insights into the decision can be shared with other employees, as the decision is not about an individual (but be sure that the role change is the real reason for the firing, otherwise it will eventually result in distrust from employees).

A role change specific to an individual feels the most personal for the person being fired and can be hardest for other employees to understand. The message of “great for previous role, wrong skills for what the company needs going forward” is easy to say, harder for employees to process, often because a good employee will be leaving, and many employees won’t have the insights into the need for the change (or may simply disagree). The best analogy I’ve been able to come up with is sports teams, where a great player may be traded to make room for a player that has different skills that make the team better as a whole (as in Moneyball, where trading stars for players that just got on base resulted in a better team).

A role change specific to an individual feels the most personal for the person being fired and can be hardest for other employees to understand. The message of “great for previous role, wrong skills for what the company needs going forward” is easy to say, harder for employees to process, often because a good employee will be leaving, and many employees won’t have the insights into the need for the change (or may simply disagree). The best analogy I’ve been able to come up with is sports teams, where a great player may be traded to make room for a player that has different skills that make the team better as a whole (as in Moneyball, where trading stars for players that just got on base resulted in a better team).

When a role change is impacting many people (typically driven by financial situations or discontinuing a product / service), explaining to the people impacted can be more comforting than when it is a single role, since the reasons don’t feel as personal (make no mistake, for the people being fired the impact will feel very personal, it just won’t feel like they were individually targeted).

Violating the Company Relationship

Every company has it’s own unique culture, principles, rules, and expectations in the relationship with each employee, and between employees. I’ll use “don’t steal” as an example, since I this is probably a common deal-breaker even in the most toxic environments.

When there is a violation of the relationship, the employee needs to be fired, otherwise the company is signaling that it isn’t an actual expectation of the relationship, or perhaps worse, that enforcement is selectively applied. In this firing the employee should not be surprised, however an employee willing to violate the relationship in one dimension is likely willing to double down and deny their responsibility in the situation. Unfortunately, this is one of those nobody wins outcomes that, as a manager, you simply need to get thorough it, look for the learning opportunity, and move-on.

A particular challenge in this type of situation is the inability to offer an explanation to other employees, especially if the violation was concealed. Using the stealing example, the company could have liability is disclosing the violation to others, so employees just see somebody fired for no apparent reason. As recommended in my guidelines above, if your company has a (trusted) transparent culture around how and why people get fired, many may infer that it was either a performance problem or violation, which a better outcome than the firing feeling random.

Management Failures

Employment is a relationship, and the manager and company have to acknowledge their responsibility in the failed relationship, both in why it failed and the importance of properly handling the failure.

Employment is a relationship, and the manager and company have to acknowledge their responsibility in the failed relationship, both in why it failed and the importance of properly handling the failure.

Passing the Buck

If there are other existing opportunities where the employee could be successful at the company, that can provide a solution that is both a win for the employee and the company. However, since firing is so unpleasant, managers should be challenged to understand if they are diverting the problem to somebody else or do they really feel the employee is best for the opportunity. Ask the question, “if the employee didn’t work here but was applying for the new opportunity, would you hire them?” If the answer isn’t a confident, “yes”, the manager is likely passing the problem to somebody else. Another red flag is the creation of a new role for an employee that would otherwise be fired… in almost every case I’ve experienced, this is a manager avoiding a tough (and necessary) decision.

Performance Improvement Plans

Performance Improvement Plans (known as “PIPs” in HR speak) are formal documentation explaining the employee’s performance problem, the expectations, a process to improve and a success evaluation date. On the surface this is all great – issues that should have been discussed in 1:1 meetings. When used as a tool with the intention of making the employee successful, PIPs can be really helpful in providing clear expectations.

The dark side of PIPs is when they are used as an HR cover your ass maneuver, in which the employee’s fate has already been decided but, because of risk or liability, there is a desire fore the company to have ample documentation around the termination. Don’t do this. When a firing outcome has been determined, fire the employee. Dragging-out a process or giving false hope is disrespectful, and arguably cruel.

Learning from Failure

A firing may not reflect a failure, it might actually be the best decision for the company and perhaps even for the person being fired. However, all firings can be an opportunity for the company to learn and improve its processes. If it was a new employee, try to understand how the interview / hiring process could have identified the issue. With longer-term employees, look for training opportunities (for the employee or management) that could have resulted in a more successful outcome. Understand when the firing should have happened and what should be done next time. Since firing has such a big impact to both the employee and the company, there is value in continually improving the process to reduce or avoid any firings that could have been saves.

Have you been on either end of the firing process and have suggestions for improving how it gets handled? Please leave a comment!

In August I presented The Challenges of Executing Lean Startup at Scale, generously hosted by Rangle.io in Toronto, Canada. Rangle is the premier digital transformation consultancy, founded on Lean Startup principles and achieving impressive growth – a really great success story. I spent some time with Nick Van Weerdenburg, Rangle’s CEO, discussing Digital Transformation.

In August I presented The Challenges of Executing Lean Startup at Scale, generously hosted by Rangle.io in Toronto, Canada. Rangle is the premier digital transformation consultancy, founded on Lean Startup principles and achieving impressive growth – a really great success story. I spent some time with Nick Van Weerdenburg, Rangle’s CEO, discussing Digital Transformation.

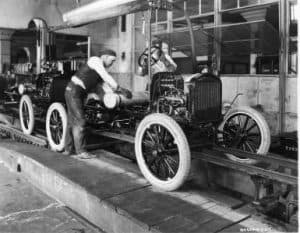

Investment-backed startups are created to discover scalable businesses, usually by inventing a new product or service that can become a large business, or by creating substantial efficiencies that take customers away from an existing large business. There is no clear, obvious path to doing either of these, otherwise success would be the expectation, not the exception. So success requires reasonable self delusion that you will succeed, as well as experimentation / rapid iteration necessary to adjust to the challenges of discovering the successful business. In practice, this can often manifest itself as the CEO coming in with the crazy idea of the day saying, “let’s try this… can we ship it by tonight?” If you like the excitement that comes from working through challenges with great uncertainty, this process can be a rewarding experience.

Investment-backed startups are created to discover scalable businesses, usually by inventing a new product or service that can become a large business, or by creating substantial efficiencies that take customers away from an existing large business. There is no clear, obvious path to doing either of these, otherwise success would be the expectation, not the exception. So success requires reasonable self delusion that you will succeed, as well as experimentation / rapid iteration necessary to adjust to the challenges of discovering the successful business. In practice, this can often manifest itself as the CEO coming in with the crazy idea of the day saying, “let’s try this… can we ship it by tonight?” If you like the excitement that comes from working through challenges with great uncertainty, this process can be a rewarding experience. Unfortunately, that particular type of person is usually the exact opposite of the particular type of person you want growing a scalable business. Growing a scalable business is more about efficiencies and optimization, much less about discovery. That same crazy idea of the day behavior that miraculously lead to discovering the scalable business is exactly what derails the consistency a company’s organizations need, and what customers will expect. As the organization grows, process and management becomes necessary to handle the challenges that come with simply trying to get hundreds of people to work towards the same goal. The needs of operating a scalable business probably contributed to the CEO quitting their previous job and creating the startup in the first place.

Unfortunately, that particular type of person is usually the exact opposite of the particular type of person you want growing a scalable business. Growing a scalable business is more about efficiencies and optimization, much less about discovery. That same crazy idea of the day behavior that miraculously lead to discovering the scalable business is exactly what derails the consistency a company’s organizations need, and what customers will expect. As the organization grows, process and management becomes necessary to handle the challenges that come with simply trying to get hundreds of people to work towards the same goal. The needs of operating a scalable business probably contributed to the CEO quitting their previous job and creating the startup in the first place. Your gut response as a startup entrepreneur is likely something like, “I’m going to make sure that doesn’t happen to me.” However, I encourage looking at it a different way… this happens, you’re probably going to be replaced, and that’s probably okay. It’s better to prepare for the possibility rather than assume it can’t happen. You may find being replaced is actually be the desired outcome if you prefer building new things rather than optimizing existing ones.

Your gut response as a startup entrepreneur is likely something like, “I’m going to make sure that doesn’t happen to me.” However, I encourage looking at it a different way… this happens, you’re probably going to be replaced, and that’s probably okay. It’s better to prepare for the possibility rather than assume it can’t happen. You may find being replaced is actually be the desired outcome if you prefer building new things rather than optimizing existing ones.

When an employee is under-performing it is their manager’s responsibility to make that employee successful and, if that fails, fire the employee. An employee’s performance should be a regular discussion with their manager, and missing expectations should be made explicitly clear, along with clarity around the exact expectations and a plan to improve. If the improvement doesn’t happen, the firing discussion should be more of a final conclusion to the mutual recognition of the problem, with both parties aligned on the shared data. My rule is, “if the employee was surprised they were fired for performance reasons, this is a failure of their manager”.

When an employee is under-performing it is their manager’s responsibility to make that employee successful and, if that fails, fire the employee. An employee’s performance should be a regular discussion with their manager, and missing expectations should be made explicitly clear, along with clarity around the exact expectations and a plan to improve. If the improvement doesn’t happen, the firing discussion should be more of a final conclusion to the mutual recognition of the problem, with both parties aligned on the shared data. My rule is, “if the employee was surprised they were fired for performance reasons, this is a failure of their manager”. A role change specific to an individual feels the most personal for the person being fired and can be hardest for other employees to understand. The message of “great for previous role, wrong skills for what the company needs going forward” is easy to say, harder for employees to process, often because a good employee will be leaving, and many employees won’t have the insights into the need for the change (or may simply disagree). The best analogy I’ve been able to come up with is sports teams, where a great player may be traded to make room for a player that has different skills that make the team better as a whole (as in

A role change specific to an individual feels the most personal for the person being fired and can be hardest for other employees to understand. The message of “great for previous role, wrong skills for what the company needs going forward” is easy to say, harder for employees to process, often because a good employee will be leaving, and many employees won’t have the insights into the need for the change (or may simply disagree). The best analogy I’ve been able to come up with is sports teams, where a great player may be traded to make room for a player that has different skills that make the team better as a whole (as in  Employment is a relationship, and the manager and company have to acknowledge their responsibility in the failed relationship, both in why it failed and the importance of properly handling the failure.

Employment is a relationship, and the manager and company have to acknowledge their responsibility in the failed relationship, both in why it failed and the importance of properly handling the failure.

Employees not understanding this component of their compensation creates an interesting challenge for an employer… I believe companies should help employees understand the value of stock options and the various nuances of how options work. However, I also believe that it wastes a limited resource to provide stock options when an employee doesn’t value them. I like everybody to have a stake in the outcome of the company, but options should be weighted so they are the most valuable to the recipient, and other forms of compensation should be used when options are not valued.

Employees not understanding this component of their compensation creates an interesting challenge for an employer… I believe companies should help employees understand the value of stock options and the various nuances of how options work. However, I also believe that it wastes a limited resource to provide stock options when an employee doesn’t value them. I like everybody to have a stake in the outcome of the company, but options should be weighted so they are the most valuable to the recipient, and other forms of compensation should be used when options are not valued. Section 1202 is surprisingly not well known – four Bay Area tax advisors I contacted were unaware of it when I referenced it. Fortunately it was mentioned in Piaw Na’s book,

Section 1202 is surprisingly not well known – four Bay Area tax advisors I contacted were unaware of it when I referenced it. Fortunately it was mentioned in Piaw Na’s book,