On January 8, 2021 Twitter permanently suspended Donald Trump’s account, joining Facebook, Instagram, and Twitch in the censorship of the President. Many prominent voices stated this is a dangerous encroachment on freedom of speech, sometimes making comparisons to China’s government censoring the people. Having operated communities of millions of users, I believe Twitter’s biggest failure was not applying its rules consistently to all users, enabling abuses to increase in magnitude and eventually requiring the drastic response of a permanent suspension. Further, a social platform that does not censor, where complete freedom of speech is guaranteed, is an idealistic vision, but would have questionable viability and is likely unwanted in practice.

I’ll start with the basics, First Amendment rights to freedom of speech prohibits the government from limiting this speech, it does not require citizens or companies to provide the same freedom. When a person or company shuts down discussion from someone on their property or platform, that person or company is exercising their freedom of speech. For the most part, nobody has an obligation to let someone else use their property so that the other person can exercise freedom of speech.

But just because companies have the right to censor people, should they? This is a more complicated question. In theory, I want unlimited free speech, a world in which censorship doesn’t happen, because inevitably those in power, the censor, now controls access to ideas and information and will likely support their preferred narrative. In practice, I’ve learned that lack of moderation will likely destroy a platform, and moderation (a softer way to say “censorship”) is actually desired by communities, both online and in society in general.

Moderation is Necessary

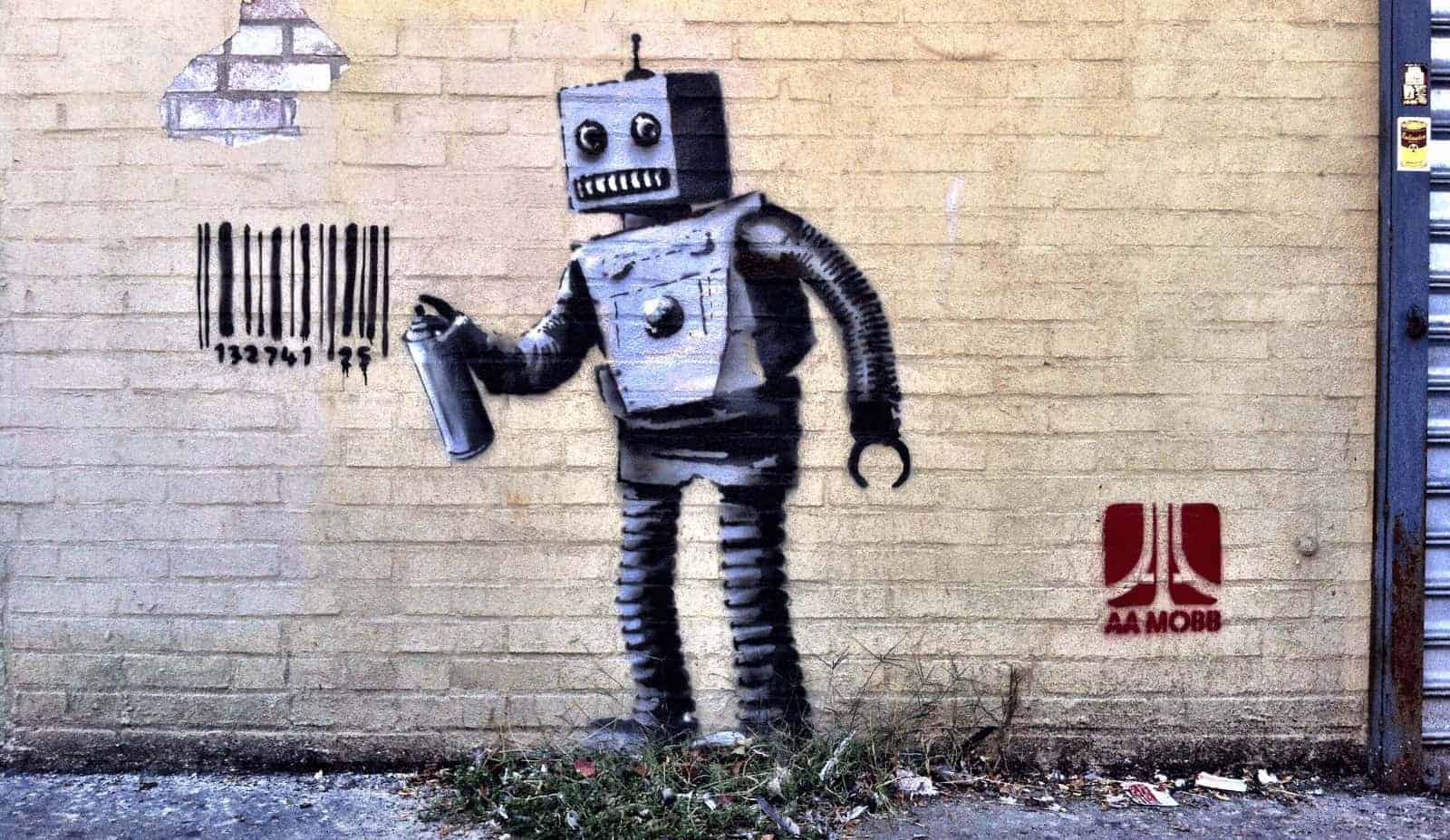

Many platforms on the Internet start open and free and eventually become moderated, and a strong driver for that moderation is the abuse of the open platform destroys the value for others. Email started off great, with an inbox filled with relevant communications and eventually turned into a signal to noise ration of about 1:150, with fake Viagra and Nigerian princes rendering email nearly useless until filtering (moderation) eliminated SPAM. Message boards and social networks become unusable when SPAM and bots infiltrate, so in addition to community moderation, there is an ongoing, continually escalating battle to validate real users vs. bots. Even friendly actors can destroy a platform – when games were popular on Facebook and developers were heavily exploiting the feed for viral growth (hey, Zynga), the real social value declined as a majority of updates were about cows from your friend’s farm, and Facebook built tools to limit this game SPAM. There is always value in exploiting these open systems at the detriment of the other users, so abuse is the natural outcome.

This community desire for moderation, whether explicit or implicit, isn’t unique to online, we see it every day in society. No matter how much freedom we want for everyone, if somebody is singing in a theater during a movie, we want them to shut up or leave. We support one’s right to share their ideas, but if they are on a bullhorn outside of our house at 4:30 AM, we want them to go away. We set our own rules for private property and have laws for public property to support this moderation.

So when Twitter took action against Trump’s accounts, this was Twitter finally enforcing its policies on a user that had consistently abused the rules they established for their platform. They finally said, “like all other users, you can’t use the bullhorn at 4:30 AM either”. I am a strong supporter in our elected officials being held to the same rules that apply to regular citizens, especially since they are often the ones imposing these rules on the citizens (anyone that has been subject to a COVID shelter in place lockdown only to see their elected officials indoor dining or world traveling understands the rage-inducing hypocrisy). The editorial decision Twitter made was not the suspension of Trump’s account, it was years and years of allowing him to violate the terms they set for their platform, allowing a slow progression to eventually becoming a tool for organizing an attack on our government. It is impossible to know what would have happened if Twitter had enforced its policies consistently years ago, but generally problems are easier to manage when you address them early instead of letting them grow in magnitude and force.

Creating an Platform Without Censorship is Difficult

But won’t censoring just drive these users to build another, more powerful network, or to hidden communities where they can’t be reached? Maybe, but it isn’t that simple. A large, functional community requires the support of many companies that are effectively gatekeepers, and they have restrictions on abuses of their platforms. If you want mobile apps, you need Apple and Google’s platforms. If you decide to be web only, you still need hosting for your servers, a CDN (how content is cached and distributed at scale) and DDOS (distributed denial of service, when people kill your servers by flooding them with traffic) attack protection, companies like Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Akamai, and Cloudflare. Cloudflare is a great example of a company that has shown extreme and sometimes controversial support against censoring any site (even some pretty horrible ones), but eventually shut down protection for a site that was organizing and celebrating the massacre of people. Each of these platforms has the ability to greatly limit the viability of a service they believe is abusive, which is exactly what happened to Parler when Apple and Google determined their lack of moderation was unacceptable. There are other possible technology solutions like decentralized networks that might be able to reduce the dependency on these other platforms, but this isn’t just a technology problem.

Beyond technology requirements, what about the financial viability of a completely open platform? Monetization introduces another set of gate keepers, from payment processors, to advertisers, and legal compliance. While there will always be some level of advertiser willing to place ads anywhere (yes, dick pills for the most part), most major advertisers don’t want to be associated with content that is considered so abusive that no major platform wants the liability of supporting it. Depending on the activities on the site, banks can be prevented from providing services to the platform, and even with legal but edgy content (e.g. porn), there is a huge cut that goes to payment processors as they take a risk in providing money exchanges. Crypto can provide some options, but it is largely not understood by the average user and, depending on the content of the site, there can be legal requirements to KYC (know your customer), and liability for profiting on the utility of the site if the content is illegal. There are potential solutions for each of these, but it gets increasingly more difficult to achieve any scale.

Building on dark web is a possibility, although still vulnerable to many of the platform needs for scale. The dark web is also the worst dark alley of the Internet, difficult to discover and navigate, and the lack of moderation would mean many abuses, from honeypots (fake sites likely setup by law enforcement to have an easy way to track suspicious behavior) to scams and exploits preying on the average user that doesn’t understand the cave they’ve wandered into.

So while Trump certainly has a large base of followers and the financial resources (well, maybe) to have one of the best chances of being a catalyst for a new platform, there are many forces outside of that platform’s control that challenge its viability.

So, What’s Next?

If I had to guess, a few of the “alternative” networks will make a land grab for the users upset by the Presidential bans. The echo chamber of everyone having the same belief may not provide the dopamine response they get from a network with extreme conflict, so it may seem less interesting for the users. I also assume the environment is ripe for people to go after the next big thing, decentralized, not subject to oversight. Ultimately, societal norms will likely limit the scale and viability of these networks, and those limitations will likely be proportional to the lack of moderation.

So, all we have to do is ensure societal norms reinforce individual liberty while not enabling atrocities on humanity. It’s that simple. 😟

Update: in the 10 hours since I wrote this, AWS (Amazon’s web hosting) decided to remove Parler from their service, which will likely take the site offline for at least several days.

Update January 10, 2021: Dave Troy (@davetroy) published a Twitter thread with the challenges specific to Parler, with details about their lack of platform options.

IMVU creates social products, connecting people using highly-expressive, animated avatars. A huge part of the value proposition is creativity and self expression, a lot of which comes from the customer’s choice of avatars and outfits. People are usually surprised to learn that the business generates well over $50 million annually. IMVU’s business model is based around monetizing that value proposition, as customers purchase avatar outfits and other customizations. However, IMVU doesn’t create this content, it is built by a subset of customers (“Creators”) for sale to other customers – IMVU provides the marketplace and facilitates the transactions. IMVU was the only entity that could create new tokens for the marketplace, so almost all of IMVU’s revenue was from customers purchasing tokens to buy virtual goods. This creates a true

IMVU creates social products, connecting people using highly-expressive, animated avatars. A huge part of the value proposition is creativity and self expression, a lot of which comes from the customer’s choice of avatars and outfits. People are usually surprised to learn that the business generates well over $50 million annually. IMVU’s business model is based around monetizing that value proposition, as customers purchase avatar outfits and other customizations. However, IMVU doesn’t create this content, it is built by a subset of customers (“Creators”) for sale to other customers – IMVU provides the marketplace and facilitates the transactions. IMVU was the only entity that could create new tokens for the marketplace, so almost all of IMVU’s revenue was from customers purchasing tokens to buy virtual goods. This creates a true  When there is a benefit to exploiting a system, people will try to exploit the system. Since the benefit in this system was real money, it didn’t take long for bad actors to surface. IMVU customers were being harmed by bad Resellers that would take their money and not provide tokens, or steal their accounts (and tokens). As a result, we locked-down the Reseller program to less than 20 trusted people and had requirements for them to maintain good practices to remain in the program. And things were good…

When there is a benefit to exploiting a system, people will try to exploit the system. Since the benefit in this system was real money, it didn’t take long for bad actors to surface. IMVU customers were being harmed by bad Resellers that would take their money and not provide tokens, or steal their accounts (and tokens). As a result, we locked-down the Reseller program to less than 20 trusted people and had requirements for them to maintain good practices to remain in the program. And things were good… The immediate pain comes from managing communication with a large, passionate community that benefits from the established system, doesn’t necessarily see the need for change, and doesn’t (and can’t) have the breadth of information necessary to understand why changes are necessary (and ultimately, beneficial). IMVU’s Community Manager made heroic efforts and did a great job with communication, but there were still massive forum threads, petitions, and doomsayers.

The immediate pain comes from managing communication with a large, passionate community that benefits from the established system, doesn’t necessarily see the need for change, and doesn’t (and can’t) have the breadth of information necessary to understand why changes are necessary (and ultimately, beneficial). IMVU’s Community Manager made heroic efforts and did a great job with communication, but there were still massive forum threads, petitions, and doomsayers. I knew the potential impact before making the decision, and exercised a lot of diligence researching the economy and token ecosystem (to be more accurate, I had an amazing COO that did the heavy lifting and we were aligned on our understanding). There were few decisions I made where I felt as confident in the ultimate result it would produce, but the timing, and seeing the painful business results each week certainly tested my confidence internally and I would review my assumptions to see where I could have gotten it wrong. Externally I remained more confident, reassuring employees and board we would see an inflection point… soon… it’s coming… hang in there.

I knew the potential impact before making the decision, and exercised a lot of diligence researching the economy and token ecosystem (to be more accurate, I had an amazing COO that did the heavy lifting and we were aligned on our understanding). There were few decisions I made where I felt as confident in the ultimate result it would produce, but the timing, and seeing the painful business results each week certainly tested my confidence internally and I would review my assumptions to see where I could have gotten it wrong. Externally I remained more confident, reassuring employees and board we would see an inflection point… soon… it’s coming… hang in there.

When you look at all of the new companies being created, the majority of these are Small Businesses. There are a few reasons for starting these, from following your passion, to having a reliable income, to perhaps creating a family business that will provide work for future generations. These companies are generally funded with family savings, small business loans, or personal loans. In almost all cases, the goal of these businesses is to be cash-flow positive and, if there is company growth, it is usually constrained by actual cash coming into the company, not spending ahead of revenue. As such, a Small Business will have revenue very early after starting, quickly as months or weeks. Owners are typically rewarded by the longevity of the company, a share of the profits, and sometimes a sale of the company.

When you look at all of the new companies being created, the majority of these are Small Businesses. There are a few reasons for starting these, from following your passion, to having a reliable income, to perhaps creating a family business that will provide work for future generations. These companies are generally funded with family savings, small business loans, or personal loans. In almost all cases, the goal of these businesses is to be cash-flow positive and, if there is company growth, it is usually constrained by actual cash coming into the company, not spending ahead of revenue. As such, a Small Business will have revenue very early after starting, quickly as months or weeks. Owners are typically rewarded by the longevity of the company, a share of the profits, and sometimes a sale of the company. While you couldn’t tell from a survey of Silicon Valley, but only a very small percentage of new companies are Startups. These are companies that have a vision to discover some radical innovation, in a product, a process, or a service, that has the ability to win a huge market. Since this is an exercise in discovery, the path of a Startup is one of uncertainty and high risk, with 9 out of 10 of these companies failing. The uncertainly means Startups need risk capital (usually multiple infusions) and can take years before they have any revenue. The most common source of funding for these companies is Venture Capital. Proving a repeatable business model and massively scaling business is the goal of Startups. Owners (shareholders) are rewarded by a liquidity event where stock in the company is converted to cash, typically through an acquisition or by having an IPO, and trading stock on the public markets.

While you couldn’t tell from a survey of Silicon Valley, but only a very small percentage of new companies are Startups. These are companies that have a vision to discover some radical innovation, in a product, a process, or a service, that has the ability to win a huge market. Since this is an exercise in discovery, the path of a Startup is one of uncertainty and high risk, with 9 out of 10 of these companies failing. The uncertainly means Startups need risk capital (usually multiple infusions) and can take years before they have any revenue. The most common source of funding for these companies is Venture Capital. Proving a repeatable business model and massively scaling business is the goal of Startups. Owners (shareholders) are rewarded by a liquidity event where stock in the company is converted to cash, typically through an acquisition or by having an IPO, and trading stock on the public markets.

IMVU had a culture of data-validated decisions from almost day one, and as a result we made it easy for anybody to create their own split test and validate the business results of their efforts. It took minutes to implement the split test and compare oh so many metrics between the cohorts. All employees had access to this system and we tested everything, all the time. A paper released in 2009,

IMVU had a culture of data-validated decisions from almost day one, and as a result we made it easy for anybody to create their own split test and validate the business results of their efforts. It took minutes to implement the split test and compare oh so many metrics between the cohorts. All employees had access to this system and we tested everything, all the time. A paper released in 2009, While numerous biases are working against you, with a buffet of metrics one of the most common is the

While numerous biases are working against you, with a buffet of metrics one of the most common is the

Within 24 hours of the breach I started receiving emails that threatened to release the customer data and publicly announce the breach if we didn’t pay a sum of money. My response to the blackmail was letting them know I would consider their proposal, but ultimately the damage they would do is to customers that didn’t deserve to be exploited, and to employees, good people that already feel a ton of weight from the responsibility. They gave me a few days to make a decision.

Within 24 hours of the breach I started receiving emails that threatened to release the customer data and publicly announce the breach if we didn’t pay a sum of money. My response to the blackmail was letting them know I would consider their proposal, but ultimately the damage they would do is to customers that didn’t deserve to be exploited, and to employees, good people that already feel a ton of weight from the responsibility. They gave me a few days to make a decision.

When asked, entrepreneurs don’t always recognize that their business model is an agency… they may see the unique customer work provided as building support in the underlying platform, or a way to help onboard early customers. While all possible, it’s unlikely, and VCs that have looked under the hood of hundreds of companies will understand the signals indicating this is an agency:

When asked, entrepreneurs don’t always recognize that their business model is an agency… they may see the unique customer work provided as building support in the underlying platform, or a way to help onboard early customers. While all possible, it’s unlikely, and VCs that have looked under the hood of hundreds of companies will understand the signals indicating this is an agency: If you do want to go the VC route and have a VC-sized exit, you’re going to either prove your business is the exception (unlikely), or make some fundamental changes to your business to achieve some combination of the following:

If you do want to go the VC route and have a VC-sized exit, you’re going to either prove your business is the exception (unlikely), or make some fundamental changes to your business to achieve some combination of the following: