I’ve been looking at a lot of products recently, mostly for very early stage companies, where one typically builds a successful product by addressing a customer’s needs, and the customer is delighted. But some product decisions, while not well received by customers (or sometimes hated), end up being better for the customer in the long term. As an example, with major version updates, customers can immediately hate re-learning a product they already knew how to use, even though the changes may result in a better experience and more customers.

A few years ago I was in the position where it was necessary to make such a product decision… I knew would be hated by my customers, it was unlikely the benefit could be communicated to them, and if the decision was wrong, it would be a disaster that could result in 100 people losing their jobs.

It was a change to the experience that powered 90% of IMVU’s revenue.

What is this IMVU Thing?

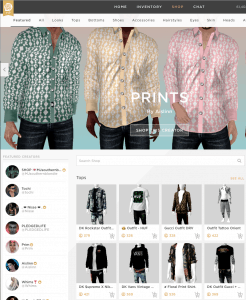

IMVU creates social products, connecting people using highly-expressive, animated avatars. A huge part of the value proposition is creativity and self expression, a lot of which comes from the customer’s choice of avatars and outfits. People are usually surprised to learn that the business generates well over $50 million annually. IMVU’s business model is based around monetizing that value proposition, as customers purchase avatar outfits and other customizations. However, IMVU doesn’t create this content, it is built by a subset of customers (“Creators”) for sale to other customers – IMVU provides the marketplace and facilitates the transactions. IMVU was the only entity that could create new tokens for the marketplace, so almost all of IMVU’s revenue was from customers purchasing tokens to buy virtual goods. This creates a true two-sided market, and one of the biggest challenges is balancing the needs of both sides of the market. Never was balancing these markets so risky as the decision to take control of the way Creators earned real-world currency through sales of their products.

IMVU creates social products, connecting people using highly-expressive, animated avatars. A huge part of the value proposition is creativity and self expression, a lot of which comes from the customer’s choice of avatars and outfits. People are usually surprised to learn that the business generates well over $50 million annually. IMVU’s business model is based around monetizing that value proposition, as customers purchase avatar outfits and other customizations. However, IMVU doesn’t create this content, it is built by a subset of customers (“Creators”) for sale to other customers – IMVU provides the marketplace and facilitates the transactions. IMVU was the only entity that could create new tokens for the marketplace, so almost all of IMVU’s revenue was from customers purchasing tokens to buy virtual goods. This creates a true two-sided market, and one of the biggest challenges is balancing the needs of both sides of the market. Never was balancing these markets so risky as the decision to take control of the way Creators earned real-world currency through sales of their products.

But First, A Little History…

Today the idea of selling virtual goods for real money is common place, as is people getting paid for creating user generated content…. examples include YouTube, Roblox, and Twitch. When IMVU was pioneering this model, there were few examples, and a lot of uncertainty around the concept of virtual goods being converted to real currency, in particular if this process would classify the company as a bank, with all of the associated banking regulations. IMVU avoided this risk by not handling any conversion of tokens to real currency, and instead allowing third parties to engage in transactions independently.

Very quickly “Resellers” popped-up, offering customers tokens for prices below what IMVU charged, and frequently purchasing tokens, enabling successful Creators to obtain real currency (IMVU took a percentage of every transaction, so the overall supply of tokens always decreased and helped keep the economy strong). This structure created a robust marketplace, where customers loved a huge catalog of items, Creators benefitted from their success, and Resellers benefitted from arbitrage.

When there is a benefit to exploiting a system, people will try to exploit the system. Since the benefit in this system was real money, it didn’t take long for bad actors to surface. IMVU customers were being harmed by bad Resellers that would take their money and not provide tokens, or steal their accounts (and tokens). As a result, we locked-down the Reseller program to less than 20 trusted people and had requirements for them to maintain good practices to remain in the program. And things were good…

When there is a benefit to exploiting a system, people will try to exploit the system. Since the benefit in this system was real money, it didn’t take long for bad actors to surface. IMVU customers were being harmed by bad Resellers that would take their money and not provide tokens, or steal their accounts (and tokens). As a result, we locked-down the Reseller program to less than 20 trusted people and had requirements for them to maintain good practices to remain in the program. And things were good…

The World Changes

Fast forward to 2015 and the world has changed… selling virtual goods and making money from user-generated content are well established practices. And, perhaps related to these practices being more mainstream, financial institutions have established best practices and requirements for these types of businesses. Mobile apps were also well established, which included customer expectations for purchasing in-app content, and app store guidelines for selling virtual goods. These developments, along with recognizing opportunities to provide more purchasing reliability to customers, drove IMVU to restructure the fundamentals of the Reseller program.

The decision to go through this restructuring was highly disruptive to customers, generally unpleasant for all involved, and absolutely the right thing for both customers and the company.

The Heart Transplant

The fundamental change was eliminating Resellers altogether, with IMVU providing royalty payments directly to Creators for the sale of their virtual goods. The process of paying content creators directly is pretty straightforward if it is your starting point, but transitioning to it is painful.

The immediate pain comes from managing communication with a large, passionate community that benefits from the established system, doesn’t necessarily see the need for change, and doesn’t (and can’t) have the breadth of information necessary to understand why changes are necessary (and ultimately, beneficial). IMVU’s Community Manager made heroic efforts and did a great job with communication, but there were still massive forum threads, petitions, and doomsayers.

The immediate pain comes from managing communication with a large, passionate community that benefits from the established system, doesn’t necessarily see the need for change, and doesn’t (and can’t) have the breadth of information necessary to understand why changes are necessary (and ultimately, beneficial). IMVU’s Community Manager made heroic efforts and did a great job with communication, but there were still massive forum threads, petitions, and doomsayers.

The next challenge is trying to do the best thing possible for the Resellers, knowing that ultimately the result is going to be eliminating their business, so all you can hope for is making the best of a crappy situation. At this point Resellers were a small oligopoly with strongly protected positions, giving them a huge advantage in both purchasing tokens from Creators and selling to customers, and many had many months of token supply in inventory. Making things even more complicated, many Creators were also uncertain about their future ability to sell tokens, and wanted a way to cash out.

The solution was to announce to the IMVU community a timeframe for the wind-down of the Reseller program, allowing Resellers a small window to purchase tokens from Creators, and a larger window to deplete their inventories. A few Resellers dumped their tokens immediately at fire sale prices, but the more savvy Resellers paced their sales, recognizing that prices would increase as supplies dwindled. A few Resellers maximized the opportunity to buy tokens from Creators at next-to-nothing prices and benefit by selling them an close-to-peak prices a few weeks later. Ultimately Resellers were able to deplete their inventories before the program end. During the two month transition, IMVU resisted discounting its own token sales as to not compete with Resellers – this choice, combined with the tokens flooding the market, had a very real impact on revenue, both in the immediate loss of token sales and in the months following, while many customers had stockpiled a large supply of discounted tokens and didn’t need to purchase from the company.

The remaining transitional work was relatively straightforward (I’d write, “simple”, but I saw several teams of people work their butts off to get everything in place and working in time). Creators needed to provide necessary documentation so they could receive payment, and IMVU needed the accounting systems and people to facilitate payments.

But it wasn’t smooth sailing yet… While IMVU was very good about tracking Reseller token supply as part of monitoring the economy, unknown was the fact that Creators had a pent-up demand to sell their tokens, and much of this demand was completely unmet by the oligopoly of Resellers. As a result, request for royalty payments were much higher than initially expected. The new process would lead to a better result for a larger number of customers, as Creators would reliably be able to receive royalties. However, this immediately meant substantially higher expenses for the company, which was already feeling the impact of lower revenue from the Reseller cash-out. No amount of spreadsheet magic could make the business results look good.

A Quick Note on Leading Through Uncertainty

I was CEO of IMVU during this transition, and I distinctly remember this period as one where I felt I may have made a catastrophic decision. Most bad decisions can be corrected if you’re responsive, and it is usually better to take action and correct if necessary vs. stagnate from analysis paralysis. However, given that the token economy was the business, getting this transition wrong was an existential problem for the company. Over a hundred employees could lose their jobs, and millions of customers could lose a product where they connect with friends.

I knew the potential impact before making the decision, and exercised a lot of diligence researching the economy and token ecosystem (to be more accurate, I had an amazing COO that did the heavy lifting and we were aligned on our understanding). There were few decisions I made where I felt as confident in the ultimate result it would produce, but the timing, and seeing the painful business results each week certainly tested my confidence internally and I would review my assumptions to see where I could have gotten it wrong. Externally I remained more confident, reassuring employees and board we would see an inflection point… soon… it’s coming… hang in there.

I knew the potential impact before making the decision, and exercised a lot of diligence researching the economy and token ecosystem (to be more accurate, I had an amazing COO that did the heavy lifting and we were aligned on our understanding). There were few decisions I made where I felt as confident in the ultimate result it would produce, but the timing, and seeing the painful business results each week certainly tested my confidence internally and I would review my assumptions to see where I could have gotten it wrong. Externally I remained more confident, reassuring employees and board we would see an inflection point… soon… it’s coming… hang in there.

I’ve heard other CEOs share stories with a similar pattern… the role requires a balance of internal self-questioning while portraying confidence externally, and the CEO rarely has the ability to share that internal conflict with others.

Results!

In the third month following the changes, IMVU hit the inflection point – the transitional business pain stabilized and started producing positive results. Taking full control of the Creator and Reseller aspects of the economy meant customers could have a reliable experience, from purchasing tokens to receiving royalties for their content. As part of the better-regulated process, there were other bad actors, scams, and negative customer experiences that were eliminated. And since there were less variables in token supply and pricing, it was much easier to maintain stability in the value of the token, a huge win for Creators, the business, and customers that ultimately benefit from a vibrant Creator marketplace.

The change to a more tightly-controlled token economy, combined with other big initiatives that were engaging new customers, resulted in a significant wave of growth and record results for IMVU’s business.

Key Takeaways

- Talking to customers is critically important! Deeply understand the core of their objectives and pain points, and make sure product changes solve for the customer’s needs.

- Be mindful that customers won’t have the breadth or depth of information necessary to recognize the real benefit of some product decisions. Sometimes what seems to be an immediately unpopular product decision is necessary to deliver a better customer experience over the long-term.

- Spend the time to get information necessary for confidence in decisions that can have significant impact, but also be humble, open to recognizing a mistake, and ready to adjust if the results aren’t there.

- With a large enough customer base it becomes impossible to solve for everybody, as occasionally their needs will conflict. Be intentional in product decisions that make these tradeoffs, solving for the best long-term customer experience for the customers your business needs.

- Unsupportive customers should be an exception… most of the time your decisions should delight your customers.

Do you have examples of product changes customers hated but ultimately produced a better experience for them? If so, I want to hear about them! Please leave a reply, below.

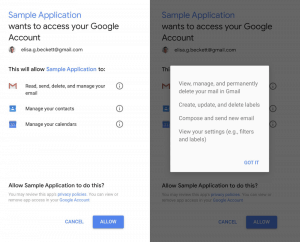

Some applications legitimately need elevated permissions to provide the service they offer, like inbox management, automatic scheduling, or even shopping deal comparisons. Many of these apps only access your data in the way necessary to provide the service, but there are many that take full advantage of access to your data and leverage your data for their benefit. According to articles on

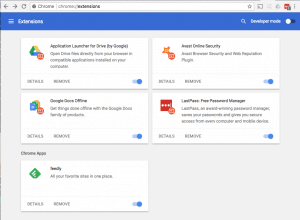

Some applications legitimately need elevated permissions to provide the service they offer, like inbox management, automatic scheduling, or even shopping deal comparisons. Many of these apps only access your data in the way necessary to provide the service, but there are many that take full advantage of access to your data and leverage your data for their benefit. According to articles on  In addition to granting companies access directly, web browser extensions can expose data from every website you visit. These Extensions in Chrome, and Add-Ons, Extensions, and Plugins in Firefox, provide enhanced functionality from password management to page translation, ad blocking, and simple video downloads. To provide these services, many extensions get access to everything you do in the browser. For example, a news feed reader has permission to “Read and change all your data on the websites you visit” – this means every page visited and all content on that page is accessible by the news reader extension… your web mail, your Facebook messages, your dating sites, medical issues you research… all available to some company that organizes news headlines for you.

In addition to granting companies access directly, web browser extensions can expose data from every website you visit. These Extensions in Chrome, and Add-Ons, Extensions, and Plugins in Firefox, provide enhanced functionality from password management to page translation, ad blocking, and simple video downloads. To provide these services, many extensions get access to everything you do in the browser. For example, a news feed reader has permission to “Read and change all your data on the websites you visit” – this means every page visited and all content on that page is accessible by the news reader extension… your web mail, your Facebook messages, your dating sites, medical issues you research… all available to some company that organizes news headlines for you. Installing applications and linked account creation on websites is simpler than ever. The downside to this ease of access is users typically spending little time scrutinizing the application. If you are giving access to your private data, spend the time to understand who is getting access, and how they will use your data. A simple web search for the application and “security” or “trust” can reveal what others experienced. If the company doesn’t have a website with the ability to contact them, and a published policy about handling your private data, there is a good chance securing your private data isn’t a real concern for them, and it should be for you!

Installing applications and linked account creation on websites is simpler than ever. The downside to this ease of access is users typically spending little time scrutinizing the application. If you are giving access to your private data, spend the time to understand who is getting access, and how they will use your data. A simple web search for the application and “security” or “trust” can reveal what others experienced. If the company doesn’t have a website with the ability to contact them, and a published policy about handling your private data, there is a good chance securing your private data isn’t a real concern for them, and it should be for you!

IMVU creates social products, connecting people using highly-expressive, animated avatars. A huge part of the value proposition is creativity and self expression, a lot of which comes from the customer’s choice of avatars and outfits. People are usually surprised to learn that the business generates well over $50 million annually. IMVU’s business model is based around monetizing that value proposition, as customers purchase avatar outfits and other customizations. However, IMVU doesn’t create this content, it is built by a subset of customers (“Creators”) for sale to other customers – IMVU provides the marketplace and facilitates the transactions. IMVU was the only entity that could create new tokens for the marketplace, so almost all of IMVU’s revenue was from customers purchasing tokens to buy virtual goods. This creates a true

IMVU creates social products, connecting people using highly-expressive, animated avatars. A huge part of the value proposition is creativity and self expression, a lot of which comes from the customer’s choice of avatars and outfits. People are usually surprised to learn that the business generates well over $50 million annually. IMVU’s business model is based around monetizing that value proposition, as customers purchase avatar outfits and other customizations. However, IMVU doesn’t create this content, it is built by a subset of customers (“Creators”) for sale to other customers – IMVU provides the marketplace and facilitates the transactions. IMVU was the only entity that could create new tokens for the marketplace, so almost all of IMVU’s revenue was from customers purchasing tokens to buy virtual goods. This creates a true  When there is a benefit to exploiting a system, people will try to exploit the system. Since the benefit in this system was real money, it didn’t take long for bad actors to surface. IMVU customers were being harmed by bad Resellers that would take their money and not provide tokens, or steal their accounts (and tokens). As a result, we locked-down the Reseller program to less than 20 trusted people and had requirements for them to maintain good practices to remain in the program. And things were good…

When there is a benefit to exploiting a system, people will try to exploit the system. Since the benefit in this system was real money, it didn’t take long for bad actors to surface. IMVU customers were being harmed by bad Resellers that would take their money and not provide tokens, or steal their accounts (and tokens). As a result, we locked-down the Reseller program to less than 20 trusted people and had requirements for them to maintain good practices to remain in the program. And things were good… The immediate pain comes from managing communication with a large, passionate community that benefits from the established system, doesn’t necessarily see the need for change, and doesn’t (and can’t) have the breadth of information necessary to understand why changes are necessary (and ultimately, beneficial). IMVU’s Community Manager made heroic efforts and did a great job with communication, but there were still massive forum threads, petitions, and doomsayers.

The immediate pain comes from managing communication with a large, passionate community that benefits from the established system, doesn’t necessarily see the need for change, and doesn’t (and can’t) have the breadth of information necessary to understand why changes are necessary (and ultimately, beneficial). IMVU’s Community Manager made heroic efforts and did a great job with communication, but there were still massive forum threads, petitions, and doomsayers. I knew the potential impact before making the decision, and exercised a lot of diligence researching the economy and token ecosystem (to be more accurate, I had an amazing COO that did the heavy lifting and we were aligned on our understanding). There were few decisions I made where I felt as confident in the ultimate result it would produce, but the timing, and seeing the painful business results each week certainly tested my confidence internally and I would review my assumptions to see where I could have gotten it wrong. Externally I remained more confident, reassuring employees and board we would see an inflection point… soon… it’s coming… hang in there.

I knew the potential impact before making the decision, and exercised a lot of diligence researching the economy and token ecosystem (to be more accurate, I had an amazing COO that did the heavy lifting and we were aligned on our understanding). There were few decisions I made where I felt as confident in the ultimate result it would produce, but the timing, and seeing the painful business results each week certainly tested my confidence internally and I would review my assumptions to see where I could have gotten it wrong. Externally I remained more confident, reassuring employees and board we would see an inflection point… soon… it’s coming… hang in there.

When you look at all of the new companies being created, the majority of these are Small Businesses. There are a few reasons for starting these, from following your passion, to having a reliable income, to perhaps creating a family business that will provide work for future generations. These companies are generally funded with family savings, small business loans, or personal loans. In almost all cases, the goal of these businesses is to be cash-flow positive and, if there is company growth, it is usually constrained by actual cash coming into the company, not spending ahead of revenue. As such, a Small Business will have revenue very early after starting, quickly as months or weeks. Owners are typically rewarded by the longevity of the company, a share of the profits, and sometimes a sale of the company.

When you look at all of the new companies being created, the majority of these are Small Businesses. There are a few reasons for starting these, from following your passion, to having a reliable income, to perhaps creating a family business that will provide work for future generations. These companies are generally funded with family savings, small business loans, or personal loans. In almost all cases, the goal of these businesses is to be cash-flow positive and, if there is company growth, it is usually constrained by actual cash coming into the company, not spending ahead of revenue. As such, a Small Business will have revenue very early after starting, quickly as months or weeks. Owners are typically rewarded by the longevity of the company, a share of the profits, and sometimes a sale of the company. While you couldn’t tell from a survey of Silicon Valley, but only a very small percentage of new companies are Startups. These are companies that have a vision to discover some radical innovation, in a product, a process, or a service, that has the ability to win a huge market. Since this is an exercise in discovery, the path of a Startup is one of uncertainty and high risk, with 9 out of 10 of these companies failing. The uncertainly means Startups need risk capital (usually multiple infusions) and can take years before they have any revenue. The most common source of funding for these companies is Venture Capital. Proving a repeatable business model and massively scaling business is the goal of Startups. Owners (shareholders) are rewarded by a liquidity event where stock in the company is converted to cash, typically through an acquisition or by having an IPO, and trading stock on the public markets.

While you couldn’t tell from a survey of Silicon Valley, but only a very small percentage of new companies are Startups. These are companies that have a vision to discover some radical innovation, in a product, a process, or a service, that has the ability to win a huge market. Since this is an exercise in discovery, the path of a Startup is one of uncertainty and high risk, with 9 out of 10 of these companies failing. The uncertainly means Startups need risk capital (usually multiple infusions) and can take years before they have any revenue. The most common source of funding for these companies is Venture Capital. Proving a repeatable business model and massively scaling business is the goal of Startups. Owners (shareholders) are rewarded by a liquidity event where stock in the company is converted to cash, typically through an acquisition or by having an IPO, and trading stock on the public markets.

IMVU had a culture of data-validated decisions from almost day one, and as a result we made it easy for anybody to create their own split test and validate the business results of their efforts. It took minutes to implement the split test and compare oh so many metrics between the cohorts. All employees had access to this system and we tested everything, all the time. A paper released in 2009,

IMVU had a culture of data-validated decisions from almost day one, and as a result we made it easy for anybody to create their own split test and validate the business results of their efforts. It took minutes to implement the split test and compare oh so many metrics between the cohorts. All employees had access to this system and we tested everything, all the time. A paper released in 2009, While numerous biases are working against you, with a buffet of metrics one of the most common is the

While numerous biases are working against you, with a buffet of metrics one of the most common is the

Within 24 hours of the breach I started receiving emails that threatened to release the customer data and publicly announce the breach if we didn’t pay a sum of money. My response to the blackmail was letting them know I would consider their proposal, but ultimately the damage they would do is to customers that didn’t deserve to be exploited, and to employees, good people that already feel a ton of weight from the responsibility. They gave me a few days to make a decision.

Within 24 hours of the breach I started receiving emails that threatened to release the customer data and publicly announce the breach if we didn’t pay a sum of money. My response to the blackmail was letting them know I would consider their proposal, but ultimately the damage they would do is to customers that didn’t deserve to be exploited, and to employees, good people that already feel a ton of weight from the responsibility. They gave me a few days to make a decision.